Rehabilitation of diaphragmatic respiration and manual traction of the cervical spine are prudent strategies to alleviate the symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). GERD is often exacerbated by insufficiency of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). Given that the diaphragm provides added anti-reflux capacity to the lower esophageal sphincter, chiropractic physicians should consider specific rehabilitative techniques to support abdominal respiration for a large subset of patients with GERD.

Estimates for the prevalence of GERD in the USA are 45% symptomatic at least once per month, 20% weekly, and 10% experiencing daily GERD symptoms.1 The hallmark symptoms are a retrosternal burning sensation (heartburn) and/or perceived reflux of gastric contents (regurgitation). While daily reflux is a normal, physiologic process without symptoms, prolonged contact of gastric acid with the esophageal epithelium causes reflux esophagitis. Esophagitis may be erosive (40%), with detectable lesions on endoscopy, or non-erosive (60%).

Physicians can diagnose GERD per history. Success with an empiric trial of histamine antagonist (Tagamet, Zantac, Pepcid) or proton-pump inhibitor (Prilosec, Prevacid, Nexium) supports a GERD diagnosis. Proton-pump inhibitors (PPI) are the mainstay of first-line medical management, acting to block the proton pump of the acid producing gastric parietal cells. While effective for symptomatic reflux esophagitis 70% of the time, the overprescription and OTC misuse of PPIs are a widespread problem.2 PPIs do not affect the physical mechanism of reflux or reduce the number of reflux events, but rather the medication increases the pH of the refluxate. As such, PPI therapy is less likely to alleviate symptoms of regurgitation without heartburn.

A careful, chiropractic evaluation should uncover any alarming symptoms, such as weight loss, angina, dysphagia, and gastrointestinal bleeding. Also, GERD may be secondary to neurologic disease affecting the neuromuscular control of swallowing. And lastly, lesions of the esophageal epithelium or tumors can cause GERD.

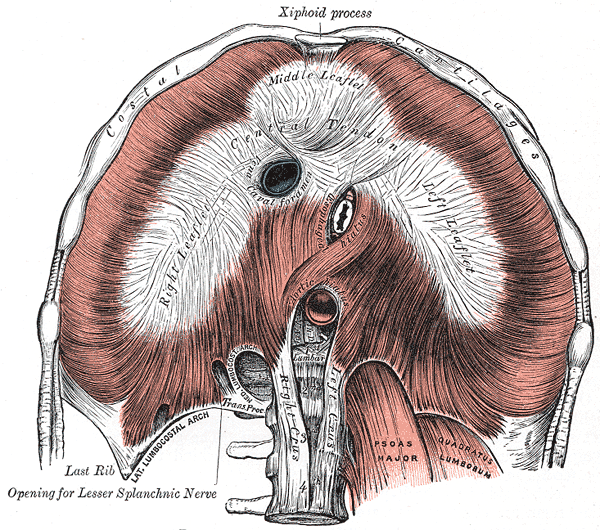

So, excluding neurological and structural causes, it is failure of the anti-reflux barrier and esophageal clearance mechanisms that result in GERD. The lower esophageal sphincter (LES) and Angle of His physically prevent reflux. Pregnancy and abdominal obesity often contribute to an obtuse angle. The LES is a bundle of tonic, circular smooth muscle fibers at the distal end of the esophagus. The LES is surrounded by the crural diaphragm. At rest, the diaphragm and LES create pressure at the distal esophagus that is greater than the intra-abdominal pressure, preventing reflux of gastric contents.3

Additionally, the diaphragm performs complex respiratory and postural function. For example, when a person lies supine, then flexes hips and knees to 90 degrees, the intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) and the LES pressure will increase concomitantly to perform the postural challenge without reflux. On the other hand, those with GERD are more likely to have a weaker increase of LES pressure given the same postural challenge.4 Underscoring the importance of the diaphragm’s contribution to the performance of the gastroesophageal function, a systematic review showed that training diaphragmatic breathing reduced GERD symptoms, improved LES pressure, decreased acid exposure, improved IAP, and reduced usage of PPI.3

While breath training for GERD is increasingly supported in the literature, the clinical benefit of training IAP may result from more than simply training the diaphragm. Recent research by Bitnar et al. shows that applying manual cervical traction while aligning the rib cage and pelvis, such that the diaphragm and pelvic bowl are parallel, immediately stimulates abdominal breathing, increases LES pressure, and improves peristaltic coordination along the entire esophagus.1

Clearly diaphragm function is a major contributor to the function of the LES as an anti-reflux barrier. And chiropractors for years have observed effective reduction of GERD symptoms following manipulative techniques. Just as stereotypical postural disturbances of the human body may result in a constellation of symptoms, the global remediation of these disturbances via a holistic clinical approach likely provides a variety of positive clinical effects. As such, the chiropractic physician is in a unique specialty to identify and care for patients in need of rehabilitative management of GERD.

- Bitnar, P., et al. “Manual Cervical Traction and Trunk Stabilization Cause Significant Changes in Upper and Lower Esophageal Sphincter: A Randomized Trial” Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics 44.4 (2021):344-351

- Gyawali CP, Fass R. Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease, Gastroenterology (2017), doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.07.049.

- Casale M, et al. Breathing training on lower esophageal sphincter as a complementary treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): a systematic review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016 Nov;20(21):4547-4552.

- Bitnar, P., et al. “Leg raise increases pressure in lower and upper esophageal sphincter among patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease.” Journal of bodywork and movement therapies 20.3 (2016): 518-524.